In his artistic practice Jeronimo Voss mostly creates installation works that can be interpreted as multilayered designs for historic and parallel worlds. By means of montages of slides and various projection methods he conjures up narrative spatial situations which are not only defined by the intermingling of the past, present, and future, but which also trace the overlapping of pictorial and social reality. Recurring focal points of his artistic exploration can be found in the cosmopolitical interpretations of astronomical hypotheses and the critical examination of neo-liberal promises of progress.

Cassandra’s Cave

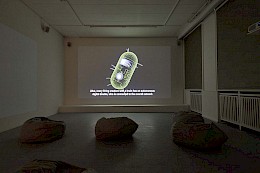

Jeronimo Voss’ new work complex Cassandra’s Cave is based on the mythological figure of the seer Cassandra (1). On the basis of her striking role as a prophet whom no one around her believed in, in his work Voss pursues the pivotal question what significance the potential of utopian prospects have for concepts and actions in our addressing of the future. To this end Voss selected seven right-angled wall elements affixed to the wall at different heights in the exhibition. Whereas in their sculptural simulation of a new space the elements loosely suggest the character of a Cassandran cave, the idea of such a protected place for developing one’s own utopias can likewise be found in the motifs of the holographic images. Not only were these photos taken from bookshelves in the living rooms of acquaintances of the artist, but the literature in them also provides a detailed historic insight into the recurring phenomena of crisis, the systematics of exploitation, and the struggle for social self-determination. Numerous topics that already are featured in the myth about Cassandra are as such clearly recognizable as fundamental elements in the history of emancipatory ideas. By the way these topics have advanced over time they similarly underline the important function of alternative visions of the future. Yet whereas the previous failure of utopian ideas of society corresponds with the pessimistic image of a Cassandra despairing at their own reality, Voss’ work at this point opens up a further prospect. Because the great overlapping of content on different people’s bookshelves ultimately makes the individual legible as part of a collective process, which contains the real potential of having a changing effect on social reality. At the same time, however, the background to Cassandra’s fate likewise illustrates a deeper-lying insight: although a different mindset with regard to the future is always based on the development of new knowledge concepts, the realization of these is never possible without defining new forms of action.

(1) In Greek mythology, Apollo gave Cassandra, the daughter of King Priam of Troy, the power of prophecy. However, after she had rejected Apollo’s advances on several occasions, he put a curse on her, upon which no one believed her prophecies any longer. Though in the battle for Troy that ensued shortly afterwards she predicted the Greeks’ war list, her knowledge could not be put to any practical benefit against the threatened destruction. For Cassandra, the community of women headed by Arisbe, which lived in a cave on Scamander River and led a life based on friendship and truthfulness, was an important retreat from a society increasingly brutalized by the war. Following the conquest of Troy, Cassandra finally made it to Mycene as a slave of King Agamemnon, where on account of her great beauty she was murdered by his jealous wife Clytemnestra.