Decolonization is not always only a matter of identity and roots, but also may involve the liberation of environment and nature. It is no secret that even today, western globalist companies are impacting the cultures, societies, and environments of Latin American countries. This imbrication of consequences are essential aspects of Marcela Armas’s artistic research. Through installations, handmade technological apparatuses, and films she investigates the mechanisms and processes of de- and re-territorialization.

TSINAMEKUTA

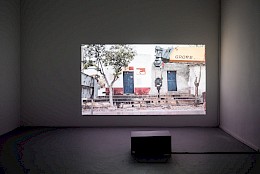

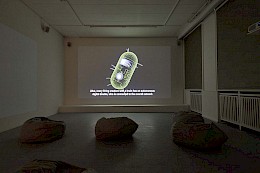

The development of the work TSINAMEKUTA (2018), conceived especially for the exhibition, took place in the region of Villa de la Paz, a municipality located in the north of San Luis Potosí in Mexico, where the traditional rural communities struggle with a growing national and transnational mining industry. In addition to mineral resources such as aluminium and copper, the soil is rich in pyrrhotite, a stone known for its intense magnetism, resulting from the unique magnetic field of this region. This phenomenon might be etched in terrestrial matter by violent changes in temperature and pressure while the reading of this magnetism might also be used to date geological strata. The rock becomes, in this sense, a trace of terrestrial memory. The pyrrhotite placed on a magnetometer in the centre of the exhibition room was taken directly from a mine in Villa de la Paz and subsequently sent to Frankfurt. The magnetometer produces a sound that varies depending on the magnetic field of the stone. A documentary film screened in the adjacent room refers to the process of extraction and presages the next step of the stone’s journey. After the exhibition, it will return back to its place of origin where it becomes part of a ceremony with a member of the Wixárika community that lives in the Altiplano Potosino. Finally, the stone will be re-magnetized by the artist with a magnetic translation of the recorded ceremony before being returned to the earth. With this process Armas gives some clue of the impact that the geo industry has on cultural and social fields. As Armas states, the “mining industry has transformed the relationship that communities have with their place of origin, being themselves absorbed as the workforce of the economic machinery that makes profane what they have ancestrally considered sacred.” She raises questions about the sense of belonging to a native land, memory and time, permanence or change, joining two records and readings of “time”: “Geological time” and “human time”. In the artist’s own words: “This project seeks an approach with some of the inhabitants, all of whom are linked to the mining industry in some way, in order to raise a space of sensibility that allows to create the tools and ways to recover the nature of spirit—as if it were a lost signal—that establishes deep bonds with life, beyond the prevailing economic relations.”